Ten Qualities of a Fine Tea

Long-term Storage of Puerh Tea

By Wu De

There is always a commotion in the world of puerh concerning the proper way to store tea and create fine vintages—a teahouse bustling with friendly discussions, arguments, laughter and wisdom in both English and Chinese alike. Like so many topics floating around the global teahouse, there are a lot of rumors, conjecture and even misinformation offered up between sips. And like most things, mastery only comes with experience. In the meantime, we have to seek out as many trustworthy sources as we can, and rely on a rational comparison of them all based on whatever experience we have acquired—although sometimes common sense and even intuition can lead us to teachers with a better, deeper understanding of these matters.

One problem we find is that, especially in the English-speaking tea world, there are too few people with real, lasting experience aging puerh. We are, of course, indebted to the few Chinese who have braved the topic in English, but otherwise most of what you read is not based on any real foundation—it’s teahouse rumors and conjecture. It seems obvious that someone who has only been storing tea for a couple of years cannot have anything of substance to say about long-term storage. We have been storing puerh for fifteen years, and yet we still would rather go to masters like Zhou Yu or Paul Lin, who have been watching tea change for more than thirty years, seeking any information on the transformation of puerh over long periods, as well as how to make sure such teas reach their highest potential. I trust their wisdom not just for its profundity and breadth alone—they have been teaching tea almost as long as I have been alive, after all—but also because I have tasted many of the teas they have aged into maturity and found them all exquisite.

Even more problematic is the idea that you can learn about aging and aged tea by drinking new tea. The tea room now is a bit rowdy with the opinions of people who have drunk little to no aged puerh. You can’t sample a few different kinds of tea from any genre and expect to have any kind of grasp on its flavor profile. I drank aged puerh from the Qing Dynasty, Antique, Masterpiece and Qi Zi eras almost daily for five years, sampling every vintage, and many of them several times, before I felt even a little confident when commenting on the characteristics of the genre itself. I really don’t mean to come off snobby or elitist in saying this. Almost all the great teas I drank weren’t ones I myself owned. I was just really fortunate to meet some of the great masters, and through no worth of my own to be given wisdom and steeped teas I often felt and/or was undeserving of. Anyway, for much of the time that I have been drinking vintage puerh it wasn’t as special or rare an experience as it is today. As I said, I don’t mean to boast; I made this point merely to express the common sense that without a lot of experience, one really should do more listening than talking. You wouldn’t expect someone to write a substantial, meaningful article on oolong tea, for example, if they hadn’t tried hundreds of kinds—enough times to develop an experiential wisdom worth listening to. Similarly, a handful of sessions with a few aged teas is not enough for one to understand the genre. And one thing all masters I’ve ever met have concordantly exclaimed is that when it comes to storing puerh tea for a long time, the only way to really understand which new teas are ideal, and how to store them properly, is to drink a whole lot of well-aged puerh.

Even more problematic is the idea that you can learn about aging and aged tea by drinking new tea. The tea room now is a bit rowdy with the opinions of people who have drunk little to no aged puerh. You can’t sample a few different kinds of tea from any genre and expect to have any kind of grasp on its flavor profile. I drank aged puerh from the Qing Dynasty, Antique, Masterpiece and Qi Zi eras almost daily for five years, sampling every vintage, and many of them several times, before I felt even a little confident when commenting on the characteristics of the genre itself. I really don’t mean to come off snobby or elitist in saying this. Almost all the great teas I drank weren’t ones I myself owned. I was just really fortunate to meet some of the great masters, and through no worth of my own to be given wisdom and steeped teas I often felt and/or was undeserving of. Anyway, for much of the time that I have been drinking vintage puerh it wasn’t as special or rare an experience as it is today. As I said, I don’t mean to boast; I made this point merely to express the common sense that without a lot of experience, one really should do more listening than talking. You wouldn’t expect someone to write a substantial, meaningful article on oolong tea, for example, if they hadn’t tried hundreds of kinds—enough times to develop an experiential wisdom worth listening to. Similarly, a handful of sessions with a few aged teas is not enough for one to understand the genre. And one thing all masters I’ve ever met have concordantly exclaimed is that when it comes to storing puerh tea for a long time, the only way to really understand which new teas are ideal, and how to store them properly, is to drink a whole lot of well-aged puerh.  The need for a substantial experiential foundation in the genre of vintage puerh in order to really explore proper storage seems rather obvious to me. The problem, however, is that the growth of the puerh industry has led to dramatic price increases of vintage puerh—to levels that are often well beyond any realistic value. Those of us who were lucky enough to drink and collect all the great vintages did so at a time when they were much cheaper than now. I paid 300 USD for my first cake of Hong Yin (Red Mark). Now they are often sold for more than $70,000. I would, of course, never pay that price even if I could afford it. This incredible price increase has effectively pushed the enjoyment of vintage puerh into the hands of the few wealthy tea lovers who can manage to pay for it. Unfortunately, the Chinese saying “those without grapes call the wine sour” all too often applies to many of the conversations one can hear as one strolls around the teahouse: some people dismissing this or that vintage more out of such jealousy than a real understanding of its nature.

The need for a substantial experiential foundation in the genre of vintage puerh in order to really explore proper storage seems rather obvious to me. The problem, however, is that the growth of the puerh industry has led to dramatic price increases of vintage puerh—to levels that are often well beyond any realistic value. Those of us who were lucky enough to drink and collect all the great vintages did so at a time when they were much cheaper than now. I paid 300 USD for my first cake of Hong Yin (Red Mark). Now they are often sold for more than $70,000. I would, of course, never pay that price even if I could afford it. This incredible price increase has effectively pushed the enjoyment of vintage puerh into the hands of the few wealthy tea lovers who can manage to pay for it. Unfortunately, the Chinese saying “those without grapes call the wine sour” all too often applies to many of the conversations one can hear as one strolls around the teahouse: some people dismissing this or that vintage more out of such jealousy than a real understanding of its nature.

Leaning heavily on the wisdom of my masters, as well as my experience drinking a whole lot of vintage teas these years, I would like to explore the controversial topic of puerh storage. Much of the topic is unknown and mysterious; but some predominant truths became clear as I had many, many conversations about storing puerh with people like Zhou Yu, Lin Ping Xiang, Chen Zhi Tong and other tea teachers, as well as various biology and agricultural professors at universities in Taiwan and in Yunnan, and even some of the old timers in Hong Kong. While we do have a decent-sized collection of old tea at the center, and I have drunk my way through all the old vintages, I still feel that these are the men we all need to be listening to, rather than the teahouse rumors that all too often lead back to urban legends, insubstantial conjecture, and worse yet, even back to vendors who are merely marketing their own products.

Wet versus Dry

Traditionally, all puerh tea was aged “wet”, and for that reason Chinese people often call wet storage, “traditional storage.” There are some well-aged teas that were dry stored, but most of them were accidental, like the famous 88 Qing Bing which was kept on a floating shelf near the ceiling due to a lack of storage space. The whole concept of intentionally dry storing puerh is therefore a relatively recent development, especially when you consider that people have been aging puerh tea for millenia.

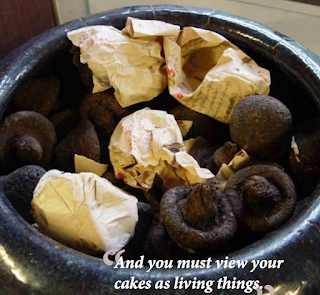

It is important to understand the difference between oxidation and fermentation—often confused by the fact that there is but one Chinese term for both: “fa xiao (發酵).” While fermentation also utilizes oxygen, it relates more to cellular breakdown caused by the presence of bacteria. Puerh tea is unique in that it is covered in bacteria: the jungle trees themselves are teeming with it, as are the villages where the tea is processed. When the cakes are steamed and compressed, more bacteria and other microorganisms make their home in the cakes. As a result, puerh cakes are truly alive—packed with colonies of fungi, bacteria and mold. Penicillium chrysogenum, Rhizopus chinensis and Aspergillus clavatus are just a few examples of mold colonies natural to puerh tea. All puerh tea is moldy, in other words. Puerh tea has always been fermented, and throughout history many ways of going about this have been developed, though storage for long periods is the oldest and best method.

In order for the bacteria to do their work, puerh needs a humid environment, some oxygen and heat. One of the reasons puerh was always stored in Southeast China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Vietnam and Malaysia is the seasonal fluctuation of these variables. In the spring, the humidity goes up and the tea absorbs more moisture. The heat of summer then encourages the fermentation process (filling the whole center with the strong fragrance of tea); the Autumn acts as a kind of buffer, as the humidity and heat decrease slowly; and then the tea “rests” in the winter, when the humidity and heat are much lower. Much more goes into storing puerh than just the humidity level, in other words. It does indeed need moisture and heat, though you might say that in order to remain healthy, the bacteria and other microorganisms in and on the tea, which cause the very fermentation that results in the magical transformation of puerh tea over time, need oxygen, humidity and heat. And that’s the tripod that supports the aging of all puerh tea. The seasonal variations only complicate the process and show with greater clarity the beauty and dexterity with which Nature wields her creative powers.

In order for the bacteria to do their work, puerh needs a humid environment, some oxygen and heat. One of the reasons puerh was always stored in Southeast China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Vietnam and Malaysia is the seasonal fluctuation of these variables. In the spring, the humidity goes up and the tea absorbs more moisture. The heat of summer then encourages the fermentation process (filling the whole center with the strong fragrance of tea); the Autumn acts as a kind of buffer, as the humidity and heat decrease slowly; and then the tea “rests” in the winter, when the humidity and heat are much lower. Much more goes into storing puerh than just the humidity level, in other words. It does indeed need moisture and heat, though you might say that in order to remain healthy, the bacteria and other microorganisms in and on the tea, which cause the very fermentation that results in the magical transformation of puerh tea over time, need oxygen, humidity and heat. And that’s the tripod that supports the aging of all puerh tea. The seasonal variations only complicate the process and show with greater clarity the beauty and dexterity with which Nature wields her creative powers.

Teas that are too dry will die. And you must view your cakes as living things. A friend recently visited us from London. Since we are both lovers of Zhou Yu’s teas, we drank some nice 2005 and 2006 cakes. He was shocked. By the end of his trip, after visiting Zhou Yu and trying some of these teas again, he said he realized that his teas were in fact dying in the part of England he lives in, as the humidity is too low and/or the seasonal fluctuations in temperature/moisture/oxygen aren’t suitable. We’ve had similar results comparing the same tea stored here and in Russia.

Today, when we say that one should “dry store” one’s high-quality teas, this means in a place where the humidity is neither too high nor too low; a place that obeys the seasonal fluctuations that makes puerh healthy, which is why I actually prefer the term “well stored” to calling such tea “dry stored”. Given the choice, though, I would take a tea that was too wet over a tea that was too dry any day of the week. We’ll get into why in a minute.

Traditionally, teahouses and collectors kept tea in basements and beneath hills to speed up the aging process. This is called “wet storage.” Most experts agree that a relative humidity of around 70% is ideal for puerh, though it may go higher seasonally and still be “dry.” Longer exposure to higher levels of humidity will speed up the fermentation and make it a “wet” tea. Wet stored tea has always been subdivided into mild, medium and heavy wet. Even those who prefer wet stored tea will agree that the first two are almost always the best, though I have seen rare examples of heavy wet teas that were excellent.

Sometimes, tea and fruit in this part of the world develop a seasonal, white mold. Finding this on vintage puerh is very common, and while it does usually signify the tea was wet stored for at least some time, depending upon the amount of mold, it is not necessarily an indication of its overall character. A short period of wet storage followed by a couple decades of drier storage might create a tea that still bears some white flakes from its period in wet storage, even though it has an overall dry profile. Unless the cake is very seriously wet, these conditions can be overcome with time, and often only affect the surface of the cake, depending on the degree of mold and how tight the compression is. I have little experience drinking any of the other kinds of mold—red, green, yellow, black, etc.—but I have heard from several different teachers that all of them are potentially unhealthy and to be avoided. We have, however, drunk gallons of the white mold— and eaten it on fruit—and so have teachers of mine for decades, without any harmful side effects. Moreover, scientists studying aged puerh in Taiwan concluded that all mold is killed in waters of eighty degrees. Anyway, if the idea of drinking bacteria, fungi or mold makes you squeamish you should get out of the puerh (and cheese) genre categorically. Even newborn, raw (sheng) puerh is covered in bacteria, and often fungi and mold as well.

Sometimes, tea and fruit in this part of the world develop a seasonal, white mold. Finding this on vintage puerh is very common, and while it does usually signify the tea was wet stored for at least some time, depending upon the amount of mold, it is not necessarily an indication of its overall character. A short period of wet storage followed by a couple decades of drier storage might create a tea that still bears some white flakes from its period in wet storage, even though it has an overall dry profile. Unless the cake is very seriously wet, these conditions can be overcome with time, and often only affect the surface of the cake, depending on the degree of mold and how tight the compression is. I have little experience drinking any of the other kinds of mold—red, green, yellow, black, etc.—but I have heard from several different teachers that all of them are potentially unhealthy and to be avoided. We have, however, drunk gallons of the white mold— and eaten it on fruit—and so have teachers of mine for decades, without any harmful side effects. Moreover, scientists studying aged puerh in Taiwan concluded that all mold is killed in waters of eighty degrees. Anyway, if the idea of drinking bacteria, fungi or mold makes you squeamish you should get out of the puerh (and cheese) genre categorically. Even newborn, raw (sheng) puerh is covered in bacteria, and often fungi and mold as well.

Actually, ripe (shou) tea is the wettest of the wet, as it is covered in mist, raked into piles and left to ferment under thermal blankets— and sometimes in unhygienic conditions (though that has improved a bit recently), far more so than any traditional wet storage warehouse. And that’s why you have to be careful purchasing shou puerh, being sure to buy from reputable sources.

Amongst those who haven’t really drunk a lot of vintage puerh, there exists this idea that wet stored tea is bad; and you’ll even hear lots of people who reject vintage puerh because of this, claiming that wet stored teas are all scams: “terrible tea”, “not worth the money”, etc. However—and that’s a big fat “however”—you never hear this from people who have been drinking vintage puerh for many years. People who love aged puerh, living in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Malaysia are all quite accustomed to drinking wet stored puerh and do not consider it to be a scam, or in any other way unworthy of attention. The fact is, since wet stored tea represents the majority of vintage tea, you might consider it a genre in and of itself— and within that genre there are both excellent and poor quality examples, exquisite wonders and garbage. Furthermore, as I said, there is a huge range of wetness, from mild to heavy. And I have never, ever been to a shop, throughout all my tea travels, with any amount of aged puerh or expertise therein that did not carry some amount of wet stored, primarily loose-leaf puerh. Never!

While most of us who have tried dry stored teas agree that they are indeed better, this doesn’t mean we don’t like wet stored tea or that we store all of our own tea in that way. Of course, people like Zhou Yu dry store all their best teas (or “store well”). No one is disputing that at all. However, we can do nothing to drastically change the state of all of the vintage teas that are in existence now; and therefore learning to enjoy them is, in part, learning about wet stored teas. As I’ve mentioned repeatedly, every lover of aged puerh I have ever met drinks wet stored teas. Since so many vintages are wet stored to some degree or another, how could they not? There is an article that we published in The Leaf Magazine written by a British traveler to China and Hong Kong in the nineteenth century, and he also describes the “mustiness” of the puerh the locals know and love.

Furthermore, not every newborn tea warrants the care and attention needed to properly store a tea. Most of the collectors I know still keep some loose teas or cakes in wet storage to speed up the process and make the tea ready for enjoyment sooner. This is not to say they dump a bucket of water on it. Who would want to ruin their tea like that? It just means the tea is put in a more humid part of the warehouse or room and left alone for longer.

One thing that I think many people with little experience drinking vintage tea sometimes don’t understand is that 99% of the people you meet who drink old tea do so for its Qi. Zhou Yu has said to me dozens of times that you’d have to be a fool to spend thousands of dollars on a flavor. You could buy a plane ticket to Switzerland and eat some of the best, fresh and warm chocolate on earth for that price! I would have to agree. If you are just after a flavorful tea, there are other, more rewarding and cheaper genres, like oolong for example. And this is what I was hinting at earlier when I mentioned that I would take a tea that was too wet over one that was too dry: Teas that are stored in places that are too dry in a sense die, losing most if not all their Qi. On the other hand, I have had plenty of wet stored teas that don’t taste great but have awesome Qi— leaving the whole body enveloped in warm, comfortable vibrations of bliss. This is not to say there aren’t incredibly delicious flavors to be had in the world of puerh: there are, and I’ve had plenty of delicious wet stored teas as well. Still, no flavor is worth spending such amounts. And when Qi becomes the predominant criteria for evaluating a tea—which it is for almost every drinker of vintage puerh I have ever met—then we often forgive some bit of mustiness, or other problems with the flavor.

No matter how careful you are, it isn’t easy to store anything well for fifty years! And many experts argue that puerh only reaches excellence at around seventy or more years, though it may be “drinkable”—well-fermented, in other words—in as little as 20-30 years, depending on how it is stored. Still, keeping anything in mint condition for decades is not easy, as any collector of antiques can testify. Just as we must forgive a dent or scratch in a hundred-year-old kettle or teapot, we must also excuse some slight misfortunes in equally-aged puerh, especially when the price candidly reflects these issues, which it does in any honest shop. If you collect vintage teapots, for example, you are of course thrilled to find a Qing pot in mint condition (though your wallet will not be as happy) but equally excited at the prospect of another specimen that costs a third of the price because there’s a chip on the inside of the lid—especially if, like us, you’re a collector that actually uses his/her pots. The same argument applies to buying vintage puerh— vintage anything—and always has!

No matter how careful you are, it isn’t easy to store anything well for fifty years! And many experts argue that puerh only reaches excellence at around seventy or more years, though it may be “drinkable”—well-fermented, in other words—in as little as 20-30 years, depending on how it is stored. Still, keeping anything in mint condition for decades is not easy, as any collector of antiques can testify. Just as we must forgive a dent or scratch in a hundred-year-old kettle or teapot, we must also excuse some slight misfortunes in equally-aged puerh, especially when the price candidly reflects these issues, which it does in any honest shop. If you collect vintage teapots, for example, you are of course thrilled to find a Qing pot in mint condition (though your wallet will not be as happy) but equally excited at the prospect of another specimen that costs a third of the price because there’s a chip on the inside of the lid—especially if, like us, you’re a collector that actually uses his/her pots. The same argument applies to buying vintage puerh— vintage anything—and always has!

Most of the mustiness in wet stored puerh tea rinses off quickly. “Last thing in is the first thing out” as Master Lin always says. A longer rinse usually takes care of it, and there are also some other brewing techniques to minimize or completely eradicate the musty flavor should you dislike it: using extra leaves is one; using charcoal and an iron tetsubin to get deeper heat that penetrates the leaves is another. There are still others… However, I have met several people around Asia who actually like that flavor. I myself prefer the taste of “well stored” teas—meaning properly stored as discussed above—and store the center’s own high quality teas in that way. Still, I cannot wave a wand over all the vintage tea out there and change it. As I drank my way through all the vintages and tons of loose-leaf teas as well, I came to appreciate that wet stored tea represents a huge category of tea, and I have had really, really wet teas that turned out to be awesome and dry ones that were not so good, and vice versa.

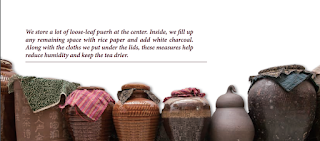

We recently found a big jar of early 80’s tuocha, for example, that were very heavily wet. This is always a good thing, because the extremely tight compression of tuochas renders their fermentation unbearably slow. We brushed the cakes off with a toothbrush and left them in the sun for an afternoon. Then, we brought them in and broke them up completely. After that, we returned them to the sun the next day for a couple hours. When they cooled, we tightly sealed them in a large, glazed pot that was completely free of odors and left them for around six months. We also added some white charcoal to help purify and absorb unwanted odors. When we opened the pot, we covered the mouth with cloth and let them sit, exposed to air, for another two weeks. Then? The tea was amazing! All the worst parts of the wet storage (the musty flavor and smell) had gone and what was left was a clear, bright tea that tasted so much older than it was—with strong Qi to boot! This is just one example of many of the awesome wet stored vintages I have had. Also, this is not the only method of “cleaning” and “revitalizing” wet stored puerh. There are others.

If we were going to spend a few thousand dollars on a well-aged cake of tea, we would of course find the cleanest, best-stored cake we could find. Nonetheless, reading or hearing such evident truths has led some people to the mistaken notion that all wet stored tea is therefore bad. If you hand me a cheap wet stored, loose-leaf tea of 50 years with awesome Qi I would be just as thrilled as with an expensive, well stored cake. And accordingly, in all my years in Asia, I’ve never met a long-term lover of vintage puerh without some wet stored teas in his or her collection. This cannot be overstated.

We must all, therefore, make a very real distinction between the way we wish to store our tea from here on out and the way in which we evaluate vintage teas that are already old. They are completely different areas of study, though you can’t have true knowledge of the one without understanding the other. We will store our newborn teas properly, which for the most part means “drier” than they were “traditionally” stored, and care for them more thoroughly—especially since newborn tea costs many times more than what it once did when most vintage teas were stored— but this does not mean that we should evaluate all vintage tea using these same criteria, or that some of those “wet stored” gems of yesteryear did not in fact turn out way better than our “dry stored” cakes ever will! Also, if you are storing your teas naturally, which, as we’ll discuss a bit further on, is really the only way, it is nigh impossible to store puerh tea in any real amount without some percentage of it getting at least mildly wet. The only environments that could truly prevent this are too dry for puerh and would cause it to die.

The saddest thing about dismissing wet stored tea entirely is that you are missing out on all the vintages of old puerh that are actually affordable, even today. I know a vendor in the West who has access to a wide variety of cheap, wet stored puerh and knowledge thereof, who told me anonymously: “I can’t sell it in the West, at least not online. Too many people would ask for a refund. They’ve been misinformed and I wouldn’t know how to combat that. It would seem, sometimes at least, that some of my customers don’t really like aged puerh, as they were very critical of teas that were only very, very mildly wet and easily corrected. Still, things are getting better. I keep such tea in the shop, and when people come in, I show them how to brew it properly and explain aged tea and Qi. Then, they get along fine.” I have heard tons of similar testimony from people who have traveled to Taiwan, tasting properly brewed wet stored tea, and learning about Cha Qi for the first time.

We paid only roughly 30 USD per tuocha for the heavy wet cakes we mentioned earlier, buying the whole jar’s worth, and the tea turned out way better than a dry stored Xiaguan tuocha we have from the same period that costs 100 USD. While there are poor wet stored teas, there also dry stored teas that aren’t very good, either. Doesn’t this hold true for any genre of tea? The first, last and only question of relevance is not whether the tea is wet or dry stored, but in fact, whether it is good tea or not!

What do we really know?

The problem with over-analyzing the storage of puerh tea, trying to seek the right parameters that can lead invariably to “well stored” tea, is that this tacitly assumes that the transformation of puerh tea over time is somehow controlled, or potentially controllable, by human beings. In fact, so many of our modern social and environmental crises revolve around similar delusions. The way that puerh tea changes from cold to warm in nature, from astringent and acidic to smooth and creamy, gathering Qi until it is aged to the point that it causes one to fall head over heels into a state of bliss—all that happens due to a completely natural process. Humans are involved; I’m not arguing that they aren’t. The center of the character for tea has the radical for Man. But when I ask all the old timers how they created these incredible “well stored” vintages of tea, they invariably exclaim “create!”—mocking my choice of words—“I didn’t do it. I just put the tea on a shelf and left it alone for fifty years.” Zhou Yu then added, “This is just one of the treasures of Nature, and no amount of explanation can make it any less mystical!” I’d have to agree: like any of you, I am anxious for more scientific research into puerh tea, and will read about the results with as much excitement as any tea lover; but there’s no explanation that can make these changes any less awe-inspiring in my view—just as no meteorological elucidation could deflate the power of the experience I had in Tibet seeing colored lights off the cliffside of a temple there!

Most of the old timers in Hong Kong, as well as Zhou Yu, Master Lin and others I have a more personal relationship with, have all showed me their warehouses and storage “techniques”. The fact is that there isn’t much method to it at all. They simply check on the tea now and again. If it smells too wet, they move it to a higher shelf. Teas they want to let age a bit slower, more “drily”, they encase in cardboard boxes, usually with a slight cutout to admit oxygen (of course, they are produced from recycled, odorless cardboard). Some, and we follow this method, even put tong-sized boxes within larger boxes, doubling the protection. For most warehouses, most of the time, the bamboo wrapping used to package seven cakes (tong) is protection enough. Still, if a tea is moldy, they brush it off and move it. Thus, checking to make sure the tea isn’t too wet or moldy is really all that goes into their “storage methodology”. Beyond that, they come into the warehouse once or twice a year and clean. Nature does the rest.

So what, then, do we really know about producing “well stored” puerh tea? Puerh needs humidity, heat and a bit of oxygen. It is best kept away from light, and of course it should not be near any kinds of odors, as it is very absorbent. Sheng and shou teas should be separated. Sometimes different vintages are separated as well, usually by age rather than kind. At times, however, it is good to have old tea with new as it helps it to age. (Maybe the bacteria and other microbes move from the well-aged tea to the newer cakes.) Check the teas now and again and move them to less humid places if they become too wet. Those teas we wish to slow down, we put in odorless cardboard. Those we wish to speed up, we put in unglazed pots on the floor with cloth over the opening, or simply keep lower down where the humidity is higher (a lower floor, lower shelf, etc.). When the tea is fermented to the desired degree, most collectors will also break it up and let it breathe in an unglazed clay jar before drinking, to expose the inner parts of the cake to more oxygen and allow the Qi to begin moving. And yet all of this assumes something implicitly: location!

The fact is that all we really know about well-aged, “well stored” teas is that they can achieve that quality in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Malaysia and to a lesser extent in a few other places. Some masters argue that many factors beyond climate are relevant to this, arguing that Feng Shui (Daoist geomancy) and other mystical forces play a part in the transformation of tea. Whether you regard any of that as important or not doesn’t matter. The fact is that all our great vintage teas at this point were stored in these places. The best ones were stored carefully, and the lower quality, often “wetter” ones weren’t— it’s really that simple. This should, in fact, come as no surprise, since there are several varieties of wine, beer and cheese that also must be fermented in special locations—not to speak of the location the grapes or other products are grown—just where the fermentation takes place. I once even read of a Belgian ale that ferments in open vats, without any additives, because of natural yeast only found in that place. Could puerh be the same?

I do think there is something to the idea of letting the fermentation happen naturally. There was an article in a Chinese magazine with a detailed comparison of some semi-aged teas. One batch had been watched carefully in the natural environs of Hong Kong and the other had been stored in a small room with an expensive machine that controlled the humidity and temperature day and night. The author argued that the natural cakes were much better than the ones stored in an “artificial” way. It makes sense to me that too much machinery, humidifiers and de-humidifiers, Storage of Puerh Tea /56 this-and-that-conditioners, would harm the tea—and definitely dampen the amount of Qi it would accumulate. No man-made anything ever compares to the creations of Nature. Furthermore, can you imagine the cost of such machinery? And the electricity bill for maintaining the perfect humidity and temperature in a room for fifty years! If you think vintage puerh is expensive now, what do you think the cost of tea stored in that way would be? Wouldn’t it have to reflect the atrocious cost of the machinery, electricity and/or maintenance over such a long period?

Does this mean that all tea stored outside Southeast Asia will be lower quality? I don’t know. No one does. We won’t know for a few decades. The fact is that the puerh boom has taken this backwater tea from Yunnan all around the globe; to places it never dreamt of going before. Furthermore, the gardens being utilized for production, the processing methods—the amazing variety of raw material (mao cha) used—all have added innumerable facets to the world of puerh that weren’t pertinent when all the current vintage puerh was produced or aged. Will these new kinds of tea age the way the great vintages did? Will they be better? Can puerh tea be aged in France? In Canada? Who knows! Many of the legendary teas, like Hong Yin for example, were notoriously disgusting when young, only to be transmuted in the cauldron of time, fueled by the fire of Nature herself. Will your teas similarly transform? I guess if you’re willing to help participate in this global experiment, then keep some tea and make sure to share your experience. But as of now, the only conclusive, factual results we have all come from Southeast Asia, so if you want to be really, completely sure, I’d just buy vintage tea stored there. I always use the analogy of stock investments: if you are only going to invest a little, then some risk is fine. But if you are going to invest a larger amount of money, you should be careful and invest in stocks that have proven their worth over time. Similarly, a few cakes here and there may be worthwhile to store wherever you are, even if the conditions seem unsuitable, just to see what happens. But if you plan on investing in larger quantities of puerh, you should really store it in Southeast Asia. Unlike any newer puerh cakes stored in other places, the vintage teas floating around are the only proven ones; and the differences in their value are relative to the original quality of the tea and the care with which they were stored in such an environment, rather than differences in the environment itself.

Does this mean that all tea stored outside Southeast Asia will be lower quality? I don’t know. No one does. We won’t know for a few decades. The fact is that the puerh boom has taken this backwater tea from Yunnan all around the globe; to places it never dreamt of going before. Furthermore, the gardens being utilized for production, the processing methods—the amazing variety of raw material (mao cha) used—all have added innumerable facets to the world of puerh that weren’t pertinent when all the current vintage puerh was produced or aged. Will these new kinds of tea age the way the great vintages did? Will they be better? Can puerh tea be aged in France? In Canada? Who knows! Many of the legendary teas, like Hong Yin for example, were notoriously disgusting when young, only to be transmuted in the cauldron of time, fueled by the fire of Nature herself. Will your teas similarly transform? I guess if you’re willing to help participate in this global experiment, then keep some tea and make sure to share your experience. But as of now, the only conclusive, factual results we have all come from Southeast Asia, so if you want to be really, completely sure, I’d just buy vintage tea stored there. I always use the analogy of stock investments: if you are only going to invest a little, then some risk is fine. But if you are going to invest a larger amount of money, you should be careful and invest in stocks that have proven their worth over time. Similarly, a few cakes here and there may be worthwhile to store wherever you are, even if the conditions seem unsuitable, just to see what happens. But if you plan on investing in larger quantities of puerh, you should really store it in Southeast Asia. Unlike any newer puerh cakes stored in other places, the vintage teas floating around are the only proven ones; and the differences in their value are relative to the original quality of the tea and the care with which they were stored in such an environment, rather than differences in the environment itself.

Above all, we need to continue sharing our experiences, and in that way grow as the world of puerh itself has done. Let us then steep another pot, call for more water; and after a few more bright cups, a smile and a laugh, fill the teahouse with more conversation, dialogue and wisdom...

The production & Processing of Puerh Tea

Puerh is unique amongst all the genres of tea because the importance of the raw material far outweighs any processing skill. The quality of most oolongs, for example, is determined as much by the source of the leaves as by the skill of the one processing the tea. The value of puerh, on the other hand, is ninety percent in the trees. There are many kinds of tea trees in Yunnan and the source determines the value of the tea. What village a tea comes from and which trees will decide its value, in other words. Of course, there is also plenty of dishonesty in the puerh world: material picked in one region and then taken to a more expensive one to be sold as native tea, young trees sold as old trees, etc. This means producers and consumers have to be able to distinguish the differences between regions and types of leaves.

Puerh trees can roughly be divided into two main categories, though it is useful to understand some of the subdivisions as well: old-growth (gu shu, 古樹) and plantation tea (tai di cha, 台地茶). Old growth tea is by far the better of these two. This refers to older trees. There is some debate about what constitutes “old-growth” since tea trees in Yunnan can range from dozens to thousands of years old. Arbitrarily, we think that when a tea tree becomes a centenarian (100 years), it can rightly be called “old-growth”. Old-growth tea can then be subdivided into trees that are wild or those that were planted by people. Though planted by man, the latter are often indistinguishable from the former as they are both found in small gardens in the heart of the forest. In fact, you would have difficulty picking the trees out from their surroundings without the help of a guide. Another subdivision could be called “ecologically-farmed old-growth”, which refers to old trees planted in gardens closer to villages and/or homesteads. Some people also like to have a category for 1,000+yearold trees as well, calling them by that name or maybe “ancient trees”. Plantation puerh (tai di cha) is far inferior and often not organic. The trees there might even be several decades old, but they aren’t Living Tea, and lack many of the qualities that make puerh so special, as we discussed in our article about this month’s tea.

Rough Tea (Mao Cha 毛茶)

All puerh tea begins with mao cha (毛茶), which translates as “rough tea”. Mao cha refers to the finished leaf as it leaves the farm to be sold directly to factories small and large, or independently at market. Tea at this stage has been plucked by hand, wilted, fried to remove the raw flavor (called “sa chin” 殺青), kneaded (ro nien, 揉捻), and dried. These processes need to occur almost immediately after the tea has been plucked, which is why they are done directly at the farm rather than at the factory.

Most varieties of tea include all the same stages of processing as puerh, though unlike puerh, the final processing often ends there and the loose-leaf tea is then packaged right at the farm. (Some oolongs were traditionally finished at shops, as well. The shop owners would do the final roasting to suit their tastes.) Puerh, on the other hand, often travels to a factory for final processing: compression into cakes if it is raw, sheng puerh or piling and then compression if it is ripe, shou puerh.

Most varieties of tea include all the same stages of processing as puerh, though unlike puerh, the final processing often ends there and the loose-leaf tea is then packaged right at the farm. (Some oolongs were traditionally finished at shops, as well. The shop owners would do the final roasting to suit their tastes.) Puerh, on the other hand, often travels to a factory for final processing: compression into cakes if it is raw, sheng puerh or piling and then compression if it is ripe, shou puerh.

Some varieties of puerh are also destined to become loose leaf. At the start, that means that they remain “mao cha”, but once they are aged, they are technically no longer “rough tea”. So an aged, loose-leaf puerh shouldn’t really be called “mao cha”.

Traditionally, these loose teas were the ones that were grown at smaller farms that didn’t have contracts with any factory—often from so-called “Border Regions” where Yunnan borders Laos, Vietnam or Myanmar. Such teas were then sold at market, traded between farmers or bought and stored by collectors. You can’t be certain, however, that a loose-leaf puerh is a Border Tea, as the big factories also packaged and sold some of their teas loose, though not as much as compressed tea. Although some of the tea that was sold loose was fine quality, most of it was considered inferior.

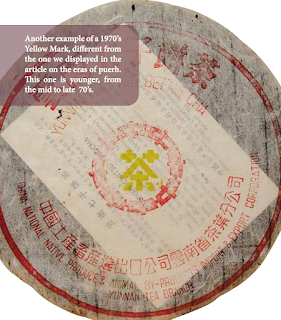

We have a huge collection of loose-leaf puerh tea here. In fact, we have so much that we have also become collectors of rare antique jars to store it all in. Loose-leaf puerh, no matter how old, is always cheaper than puerh compressed into cakes. One reason for this is that the cakes have an easily-verified vintage. Though there are fakes, experts have developed systems of identifying them, using a combination of factors from a kind of “wrapperology”, which identifies characteristic marks, color changes, etc., in the printing of the wrappers to the cake itself—its shape, leaf color or size, compression, etc. On the other hand, very few aged loose-leaf teas are pure. Most of them are blends. Some were blended during production, though more often, tea was added later on to increase the quantity of an aged tea. Sometimes blends of wet and drierstored teas, or even sheng and shou are mixed to make a tea seem older than it is. When drinking aged loose-leaf puerh, it is a good idea to only rank them relative to other loose-leaf puerhs, rather than believing in the date the merchant has given. While some loose-leaf puerhs do have a distinct vintage, most are blends. Looking at the wet leaves after steeping will also verify this.

Beyond that, cakes have been found to have more Qi than loose leaf puerh, so that if the same tea were left loose and processed into a discus (bing, 餅), for example, and then aged for thirty years, the cake would have more Qi than the loose leaf. Having done several experiments where we stored the same exact tea from the same farm in both loose leaf and cake form, we can say for sure that the compressed teas age better, and not just in terms of Qi. They are better in every way: flavor, aroma, etc. They also age faster and more evenly. One possible reason for this is that the steam used to compress the cakes seals the bacteria in, and the inner moisture creates a better environment for them to do their work. Still, despite the fact that cakes are better, loose-leaf teas are often great deals since they are much cheaper than cakes of the same age. It’s like choosing a more affordable antique teapot with a chip under the lid versus a perfect, very expensive one. Depending on your budget, the former may be the better choice.

Processing

The freshly plucked leaves are carried back to the house or village and gently spread out on bamboo mats to be slightly wilted before they are heated to remove the raw flavor. The purpose of wilting the leaves is to slightly reduce the moisture content in the leaves so that they will be more pliable and less likely to be damaged when they are heated. This process must be watched carefully so that the leaves do not oxidize more than is absolutely necessary. For that reason, wilting typically takes place outdoors and indoors. The tea is withered outdoors for some time and then placed in a well-ventilated room, often shared by members of a particular farming village.

The heating process/firing (sa chin) is literally performed to remove the raw flavor of the tea leaf. This occurs in the production of most all kinds of tea (except white tea, which categorically skips this process). In Yunnan, the heating process is still often done by hand in large woodfired woks. The temperature must remain constant and the leaves have to be continuously turned to prevent any singeing. In larger farms, though not often in Yunnan, this is done in large barrel-like machines that spin around like a clothes drier. With puerh, however, the firing is still done by hand, once again lending tradition and wisdom to the puerh process. Workers sift the leaves around in circular motions ensuring that they never touch the wok for longer than a blink. Through generations of experience the farmers can tell by appearance and feel when the leaves are sufficiently cooked, and their timing is as impeccable as any time/temperature-controlled machine elsewhere. Scientifically, the process is removing certain green enzymes within the leaf that lend it the raw flavor, which in some varieties is too bitter to be drunk. As we’ll discuss later, the sa chin of puerh is less-pronounced than in many other kinds of teas.

The heating process/firing (sa chin) is literally performed to remove the raw flavor of the tea leaf. This occurs in the production of most all kinds of tea (except white tea, which categorically skips this process). In Yunnan, the heating process is still often done by hand in large woodfired woks. The temperature must remain constant and the leaves have to be continuously turned to prevent any singeing. In larger farms, though not often in Yunnan, this is done in large barrel-like machines that spin around like a clothes drier. With puerh, however, the firing is still done by hand, once again lending tradition and wisdom to the puerh process. Workers sift the leaves around in circular motions ensuring that they never touch the wok for longer than a blink. Through generations of experience the farmers can tell by appearance and feel when the leaves are sufficiently cooked, and their timing is as impeccable as any time/temperature-controlled machine elsewhere. Scientifically, the process is removing certain green enzymes within the leaf that lend it the raw flavor, which in some varieties is too bitter to be drunk. As we’ll discuss later, the sa chin of puerh is less-pronounced than in many other kinds of teas.

After the leaves are fried they are kneaded (ro nien). This process also occurs by hand on most puerh farms or villages near old trees. A special technique is used to knead the leaves like dough. This bruises the leaves and breaks apart their cellular structure to encourage oxidation, and later fermentation (fa xiao, 發酵), which will occur through the various methods (explained in the box about sheng and shou puerh on the opposit page). It takes skill and method to achieve a gentle bruising without tearing the leaves. We have personally tried this in Yunnan and Taiwan, and found it is very difficult to achieve. We invariably tore up the leaves. The farmers, however, can go through the movements with surprising speed.

Finally, after the mao cha has been kneaded and bruised it is left to dry in the sun. Once again this process must be monitored carefully to prevent any unwanted oxidation or fermentation from occurring. Usually, the leaves are dried in the early morning and late evening sun, as midday is too hot. They will move the leaves into the same well-ventilated room used earlier for wilting during the hot hours of the day. The leaves will be inspected hourly and when they have dried sufficiently, they will be bagged and taken to the factory to be processed, or to market to be sold as loose leaf.

The two most distinguishing aspects of puerh production are the sa chin and the sun drying. The firing of puerh tea does arrest oxidation, as in all tea, but it is usually less pronounced than other kinds of tea, leaving some of the enzymes in the tea alive, as they help promote fermentation. Then, after firing and rolling, puerh is sun dried. This gives it a certain flavor, texture and aroma and helps further the natural vibrations present in the tea. Not all puerh is processed in this way, especially with all the innovation and change in the modern industry—though, ideally, we want tea made in traditional ways.

Once the leaves are processed, they will often go through their first sorting (fan ji). A second sorting will occur later at the factory itself. This sorting is to remove unwanted, ripped or torn leaves, as well as the leaves that weren’t fired or rolled properly. At this stage, the factory/ producer may ask the farmer to sort the leaves according to size, called “grade”. This practice is becoming rarer, however, as the prices of oldgrowth puerh increase. Nowadays, farmers sell most everything. Sometimes, they don’t even sort out the broken or mis-processed leaves.

At the Factory

Upon arrival to the factory, the mao cha goes through its second sorting (fan ji). This is often done by hand even at the larger factories, though some have large winnowing machines. And most have strict rules controlling the diet of the sorters. Tea is an extremely absorbent leaf and will be altered by any impurities. Sorters therefore shouldn’t eat chili, garlic or onions. Nor can they drink alcohol the night before a sort, as it will be secreted through their skin and contaminate the leaves. The sorting that occurred on the farm was more cursory and based solely on leaf size or “grade”. This second sorting is more detailed and thorough. The leaves are distinguished not only by their size, but also by their quality, type (old or young growth, which mountain they came from, etc.), and other criteria that are constantly changing. Larger factories often have mao cha arriving from all over Yunnan and therefore employ experts to monitor all sorts of conditions to determine which leaf size, which locations, etc., will have a good harvest that year. More and more, factories are targeting collectors by creating limited edition sets, with cakes from certain mountains, for example.

There is a lot of discussion nowadays about the differences between single-region and blended puerhs. For the last fifty years, most all puerhs were blends. The factories would collect the mao cha from various regions and then blend them in ways they thought improved the tea: choosing strength and Qi from one region, blended with sweetness and flavor from another, etc. In this way, cakes would be more balanced. In the last fifteen years, there has been a trend towards single-region cakes, and with it the idea that such tea is more pure. It should be remembered that all old-growth puerh is actually a blend, since no two trees are the same. So even tea from a single mountain will be a blend of different teas. If you are sensitive enough, you can even distinguish the leaves from the eastern and western side of a single tree, since they receive different sunlight. There are merits to both kinds of cakes, and it seems pointless to say that one is better than the other in general. It would be better to talk about specific teas, as a certain blended cake may be better than a given single-region cake or vice versa.

There is a lot of discussion nowadays about the differences between single-region and blended puerhs. For the last fifty years, most all puerhs were blends. The factories would collect the mao cha from various regions and then blend them in ways they thought improved the tea: choosing strength and Qi from one region, blended with sweetness and flavor from another, etc. In this way, cakes would be more balanced. In the last fifteen years, there has been a trend towards single-region cakes, and with it the idea that such tea is more pure. It should be remembered that all old-growth puerh is actually a blend, since no two trees are the same. So even tea from a single mountain will be a blend of different teas. If you are sensitive enough, you can even distinguish the leaves from the eastern and western side of a single tree, since they receive different sunlight. There are merits to both kinds of cakes, and it seems pointless to say that one is better than the other in general. It would be better to talk about specific teas, as a certain blended cake may be better than a given single-region cake or vice versa.

The trend towards boutique, private and single-region cakes has also changed the way that puerh is produced. For example, some cakes are made on site and completely processed by the farmers themselves. Most tea, however, still travels to factories for sorting (blending) and compression. What was once one of the simplest teas, at least as far as processing goes, has now become complicated by the vast industry that has grown up around it.

Mao cha can sit in a factory for a long or short time, depending on many factors. In doing so, it technically ceases to be “rough tea”. Sometimes tea is aged for a while and then piled to produce a nice, mellower shou tea than a new tea could produce. Other times the tea that was inferior and didn’t make it into a cake, is then sold loose leaf later, and labeled “aged” to help market it.

Once ready, the leaves are carefully weighed and placed into cloth compression bags or metal pans. The texture of these bags can be seen imprinted on puerh tea if one looks closely. They are not used to package the tea, only in the compression process itself. They are made from special cross-woven cotton. Strangely, even the larger factories that we’ve visited still use antique-looking scales to do their weighing. Along with human error, this explains why even new cakes are often incorrect in either direction by a decimal of a gram (of course in aged tea this is usually due to pieces breaking off).

Steam is used to prepare the tea for compression. The steam is carefully controlled—mostly automatous in the larger factories—to ensure the leaves are soft and pliable, but not cooked or oxidized in any way. It is basically a process of slight rehydration. The steam softens the tea and the cloth in preparation for compression. Sometimes the steaming takes place before the tea is placed into the cloth, using metal pans instead. In a non-mechanized factory a wooden table is placed over a heated wok full of water. The steam rises through a small hole in the center. This is far more difficult than the automatic steam generators at larger factories because the temperature control is lacking and the leaves can end up being burnt. It requires the skill of generations to successfully steam the tea this way.

The compression process was traditionally done with stone block molds. The tea is placed in the cloth, which is then turned and shaped into a ball. The nei fei is added at this time—an “inner trademark ticket” compressed into the tea to establish branding. The cloth is then twisted shut and covered with a stone mold block. The producer would then physically stand on the stone block and use his or her weight to compress the cake. In some of the smaller family-run factories, puerh cakes are still created using this method. On our recent visit to Yunnan, we had the chance to make our cakes by dancing around on the stone molds, to the delight of the Chinese audience present. Larger factories often have machines for compressing their cakes, though some still produce some of their cakes in the traditional way. Some are hand-operated presses that require the operator to pull down a lever and press the cake into shape; others are automatic and occur with the press of a button. We even saw one machine that was capable of compressing twelve bings simultaneously.

After compression, the cakes are taken out of the compression cloths and placed on wooden shelves to dry. They are still slightly damp from the steam at this stage. Many larger factories have a separate room with tons of shelves lined with drying cakes. The cakes are monitored and often even stored on particular shelves that are numbered according to their processing time. Different types of puerh leaves and different shapes or levels of compression will affect the amount of time that is needed to dry the cakes, from hours to days and sometimes even up to a week. Some big factories use ventilation systems and/or fans to speed up the process.

When they are finished drying, the cakes are taken off the shelves to be packaged. Each generation of cakes has its own unique characteristics with regards to the wrapping paper, printing, style of Chinese characters, nei fei, etc. As we discussed earlier, there is a whole science of “wrapperology”. Each decade brought revolutions in the printing process worldwide, so it seems obvious that the larger factories would change their printing methods. Also, the wrapping paper in particular is handmade, and a lot can be discerned via fibers, texture, and the appearance of the paper as well as the ink color. It is impossible to forge many of these paper and ink combinations and make them appear aged.

Discus-shaped cakes, called “bingchas” are individually wrapped in handmade paper and then bundled in groups of seven (qi zi, 七子) called tongs (桶). Each tong is wrapped in Bamboo bark (tsu tze ka, 竹子殼). Sometimes English articles mistakenly assume that these are bamboo leaves. Actually, bamboo trees shed their skin whenever they get bigger or sprout new stems. You can see this material covering the floor of any bamboo forest. The Bamboo bark conserves the freshness of the tea and makes packaging easier. Twelve tongs are then further wrapped using Bamboo, into a jian (件), which is twelve tongs of seven, so eighty-four bings in all. Other shapes of compression include bricks (zhuan), mushrooms (which look like hearts to the Tibetans they were primarily exported to, and thus named “jing cha”), bowl or nest shapes (tuocha), and sometimes melons. We have found that the discus-shaped cakes (bings) age the best.

Puerh production may seem complicated at first, but it really isn’t that difficult to understand. We hope that the basics we’ve covered in this article, along with the accompanying charts, will help simplify the process for you and increase your understanding of the more linear aspects of puerh tea. By including other articles about the energetics of puerh in this issue, as well as past and future issues, we hope to fulfill you in a more balanced way. Thus, our understanding of puerh will be more holistic, including its history, production methodologies and other informative approaches along with a spiritual and vibrational understanding of this amazing tea.

No comments:

Post a Comment